Performance Management - Quick Guide

Performance Management - Introduction

Performance management can be defined as a systematic process to improve organizational performance by developing the performance of individuals and teams working with an organization. It is a means of getting better results from the organization, teams and individuals by understanding and managing their performance within a framework of planned goals, standards and competence requirements. In other words, performance management is the process of managing an organization’s management strategy. This is how plans are converted into desired outcomes in organizations.

Performance management is a powerful tool

Performance management is a difficult role to play. Some people have difficulty when it comes to performance evaluation. Performance management is about motivation and partnership. When this kind of prospective is shared with your employees and they learn to see in that way, performance management becomes a powerful tool that will help your team to become more successful.

Performance Management is NOT Human Resource Planning

Performance management is sometimes mistaken for human resources and personnel system, but it is very different when it comes to execution. Performance management comprises of the methodologies, processes, software tools, and systems that manage the performance of an organization, whereas Human Resource Planning only takes care of individual employee’s work responsibilities and work delivery.

The benefits of performance management extend to enhancing broad cross-functional involvement in decision-making, and calculated risk-taking by providing greater visibility with accurate and relevant information, to execute an organization’s strategy.

Performance management involves many managerial roles, which shows you must be a communicator, a leader and a collaborator as well. Each individual in the team should understand exactly what their responsibilities are and what the expectations from them are, and how to work accordingly to reach the goals.

Scope and Uses

Many organizations jump from one improvement program to another, hoping that one of them will provide that big, elusive result. Most managers would acknowledge that pulling levers for improvement rarely results in a long-term sustained change. The key to improving is integrating and balancing multiple programs sustainably. You cannot break the chain by simply implementing one improvement program and exclude the other programs and initiatives.

There should be a strong bonding between the issues and the strategy of an organization. The manner in which an organization implements performance management can be influenced by its history, goals, mission, vision, strategic priorities, and the various problems it faces in its economic, political, demographic and technological environment.

Performance management is not free floating. If we simplify a little, performance management only exists to help the organization achieve its strategy in the best possible way to help the organization to survive and compete in the market.

Performance management has no end point. Sometimes, for busy, hardworking managers it seems like it is the reason we go through appraisal with staff and get the appraisal process done. Strong and improving performance by individuals and excellent performance management by all managers who are responsible to hold on with their teams are essential to achieving organizational goals.

Research has indicated that a great majority of individuals wants to perform excellently. When managers manage their teams and individual’s performance skillfully, this motivates individuals to be proud of what they do. Although this is a big generalization, it does look that most individuals really do want to do a good job, making our leadership in performance management a real-time opportunity.

Performance Management - Aims

Performance management is about aligning individual objectives to organizational objectives and ensuring that individuals hold the corporate core values. It provides for expectations to be defined in terms of role responsibilities and accountabilities expected to do, skills expected to have and behavior expected to be.

The overall aim of performance management is to establish a good culture in which individuals and teams take responsibility for the improvement of their own skills and their organizations.

Specifically, performance management is all about achieving the individual objectives according to the organizational objectives and ensuring that every individual is working towards it.

Another aim is to develop the capacity of individuals to meet the expectations of the organization. Mainly, performance management is concerned with the support and guidance for the people who need to develop.

The main points of view towards achieving the aims of performance managements are −

Empowering, motivating and rewarding employees to perform their best for the organization.

Focusing on employees’ tasks, the right things and make them doing right. Aligning everyone’s individual goals towards the goals of the organization.

Proactively managing and resourcing performance against objectives of the organizations.

Linking job performance to the achievement of the council’s corporate strategy and service plans.

The alignment of individual objectives with team, department and corporate plans. The presentation of objectives with clearly defined goals using measures, both soft and numeric. The monitoring of performance and tasking of continuous action as required.

All individuals being clear about what they need to achieve and expected standards, and how that contributes to the overall success of the organization; receiving regular, fair, accurate feedback and coaching to stretch and motivate them to achieve their best.

Performance Management - Characteristics

Performance management is a pre-planned process of which the primary elements are agreement, measurement and feedback.

The following are the characteristics of performance management −

Measures outputs of delivered performance

It is concerned with measuring outputs of delivered performance compared with expectations expressed as objectives. Its complete focus is on targets, standards and performance measures. It is based on the agreement of role requirements, objectives and performance improvement and personal development plans.

Concerned with inputs and values

Performance management is also concerned with inputs and values. The inputs are the knowledge, skills and behaviors required to produce the expected results from the individuals.

Continuous and flexible process

Performance management is a continuous and flexible process that involves managers and those whom they manage acting as partners within a framework that sets out how they can best work together to achieve the required results.

Based on the principle of management by contract and agreement

It is based on the principle of management by contract and agreement rather than management by command. It relies on consensus and cooperation rather than control or coercion.

Focuses on future performance planning and improvement

Performance management also focuses on future performance planning and improvement rather than on retrospective performance appraisal. It functions as a continuous and evolutionary process, in which performance improves over the period of time; and provides the basis for regular and frequent dialogues between managers and individuals about performance and development needs.

Performance Management - Concerns

The following are the main concerns of performance management −

Concern with outputs, process and inputs

Performance management is concerned with outputs (the achievement of results) and outcomes (the impact made on performance). But it is also concerned with the processes required to achieve these results (competencies) and the inputs in terms of capabilities (knowledge, skill and competence) expected from the teams and individuals involved.

Concern with planning

Performance management is concerned with planning ahead to achieve success in future. This means defining expectations expressed as objectives and in business plans.

Concern with measurement and review

If you can’t measure it, you can’t manage it. Performance management is concerned with the measurement of results and with reviewing progress towards achieving objectives as a basis for action.

Concern with continuous improvement

Concern with continuous improvement is based on the belief that continuously striving to reach higher standards in every part of the organization will provide a series of incremental gains that will build superior performance.

This means clarifying what organizational, team and individual effectiveness look like and taking steps to ensure that those defined levels of effectiveness are achieved. Establishing a culture in which managers, individuals and groups take responsibility for the continuous improvement of business processes and of their own skills, competencies and contribution.

Concern with continuous development

Performance management is concerned with creating a culture in which organizational and individual learning and development is a continuous process. It provides means for the integration of learning and work so that everyone learns from the successes and challenges inherent in their day-to-day activities.

Concern for communication

Performance management is concerned with communication. This is done by creating a climate in which a continuing dialogue between managers and the members of their teams takes place to define expectations and share information on the organization’s mission, values and objectives. It establishes mutual understanding of what is to be achieved and a framework for managing and developing people to ensure that it will be achieved.

Concern for stakeholders

Performance management is concerned with satisfying the needs and expectations of all the organization’s stakeholders, management, employees, customers, suppliers and the general public. In particular, employees are treated as partners in the enterprise whose interests are respected, whose opinions are sought and listened to, and who are encouraged to contribute to the formulation of objectives and plans for their team and for themselves.

Concern for transparency

Four ethical principles that should govern the operation of the performance management process. These are −

- Respect for the individual

- Mutual respect

- Procedural fairness

- Transparency of decision making

Understanding Performance

What is Performance?

Performance could be defined simply in terms of the achievement of quantified objectives. But performance is not only a matter of what people achieve but also how they are achieving it. A high performance result comes from appropriate behavior and the effective use of required knowledge, skills and competencies.

Performance management must examine how results are attained because this provides the information necessary to consider what needs to be done to improve those results. The concept of performance has been expressed by Brumbrach (1988) as follows: ‘Performance means both behaviors and results. Behavior emanates from the performer and transforms performance from abstraction to action.

Not just the instruments for results, behavior is also an outcome in its own right – the product of mental and physical effort applied to tasks – and can be judged apart from results. This definition of performance leads to the conclusion that when managing performance both behavior and results need to be considered.

It is not a question of simply considering the achievement of targets as used to happen in management-by-objectives scheme. Competence factors need to be included in the process. This is the so-called ‘mixed model’ of performance management, which covers the achievement of expected levels of competence as well as objective setting and review.

Significance of Performance

Performance is all about the core values of the organization. This is an aspect of behavior but it focuses on what people do to realize core values such as concern for quality, concern for people, concern for equal opportunity and operating ethically. It means converting espoused values into values in use: ensuring that the rhetoric becomes reality.

Meaning of Alignment

One of the most important purposes of performance management is to assign individual and organizational objectives. This means what people do at work leads to the achievement of organizational goals.

The real concept of performance is associated with an approach to creating a particular vision of purpose and aims of the organization, which will be helping each employee to understand and recognize their part of responsibilities by the help of which they will manage and enhance the performance of both individuals and the organization.

In an organization, alignment is a flow of objectives from the top to bottom and at each level, team or individual objectives are defined in comparison with higher-level goals. But it also should be a transparent process where individuals and teams are being given the opportunity to set their own goals within the framework defined by the purpose, strategy and values of the organization.

Objectives should be agreed, not set, and this agreement should be reached through the open dialogues that take place between managers and individuals throughout the year. In other words, this needs to be seen as a partnership in which responsibility is shared and mutual expectations are defined.

Managing Expectations

Performance management is essentially about the management of expectations. It creates a shared understanding of what is required to improve performance and how this will be achieved by clarifying and agreeing what people are expected to do and how they are expected to behave and uses these agreements as the basis for measurement, review and the preparation of plans for performance improvement and development.

The Significance of Discretionary Behavior

Performance management is concerned with the encouragement of productive discretionary behavior. Discretionary behavior refers to the choices that people make about how they carry out their work and the amount of effort, care, innovation and productive behavior they display.

It is the difference between people just doing a job and people doing a great job.

Performance Mnmgt - Guiding Principles

After a research conducted in 2011, researchers found out that the practitioners of performance management were of the following views −

We are expecting the line managers to recognize performance management as a useful contribution to the management of their teams rather than a chore.

Managing performance is about coaching, guiding, motivating and rewarding colleagues to help unleash potential and improve organizational performance. Where it works well it is built on excellent leadership and high quality coaching relationships between managers and teams.

Performance management is designed to ensure that what we do is guided by our values and is relevant to the purposes of the organization.

Guiding Principles of Performance Management

It is necessary to identify any causes that are external to the job and outside the control of either the manager or the individual. Any factors that are within the control of the individual and the manager can then be considered.

First, the entire performance management process – coaching, counselling, feedback, tracking, recognition, and so forth – should encourage development. Ideally, team members grow and develop through these interactions. Second, when managers and team members ask what they need — to be able to do to do bigger and better things — they move to strategic development.

The researchers also got the following additional views from practitioners about performance management −

- A management tool which helps managers to manage.

- Driven by corporate purpose and values.

- To obtain solutions that work.

- Only interested in things you can do something about and get a visible improvement.

- Focus on changing behavior rather than paperwork.

- It’s about how we manage people – it’s not a system.

- Performance management is what managers do: a natural process of management.

- Based on accepted principles but operates flexibly.

- Success depends on what the organization is and needs to be in its performance culture.

Performance Management is NOT Performance Appraisal

It is sometimes assumed that performance appraisal is the same thing as performance management. But there are significant differences.

Performance appraisal can be defined as the formal assessment and rating of individuals by their managers at, usually, an annual review meeting.

In contrast, performance management is a continuous and much wider, more comprehensive and more natural process of management that clarifies mutual expectations, emphasizes the support role of managers who are expected to act as coaches rather than judges and focuses on the future.

Performance appraisal has been discredited because too often, it has been operated as a top-down and largely bureaucratic system owned by the HR department rather than by line managers. It was often backward looking, concentrating on what had gone wrong, rather than looking forward to future development needs.

Performance appraisal schemes existed in isolation. There was little or no link between them and the needs of the business. Line managers have frequently rejected performance appraisal schemes as being time consuming and irrelevant. Employees have resented the superficial nature with which appraisals have been conducted by managers who lack the skills required.

Psychological Contract with Performance Management

The concept of psychological contract is a system of beliefs that encompass the actions employees believe are expected of them and what response they expect in return from their employer. It is concerned with assumptions, expectations, promises and mutual obligations. Psychological contracts are ‘promissory and reciprocal, offering a commitment to some behavior on the part of the employee, in return for some action on the part of the employer.

A positive psychological contract is one in which both parties – the employee and the employer, the individual and the manager – agree on mutual expectations and pursue courses of action that provide for those expectations to be realized.

A positive psychological contract is worth taking seriously because it is strongly linked to higher commitment to the organization, higher employee satisfaction and better employment relations. Performance management has an important part to play in developing a positive psychological contract.

Performance management processes can help to clarify the psychological contract and make it more positive by −

Providing a basis for the joint agreement and definition of roles.

Communicating expectations in the form of targets, standards of performance, behavioral requirements (competencies) and upholding core values.

Obtaining agreement on the contribution both parties have to make to get the results expected.

Defining the level of support to be exercised by managers.

Providing rewards that reinforce the messages about expectations.

Giving employees opportunities at performance review discussions to clarify points about their work.

Performance Management - Process

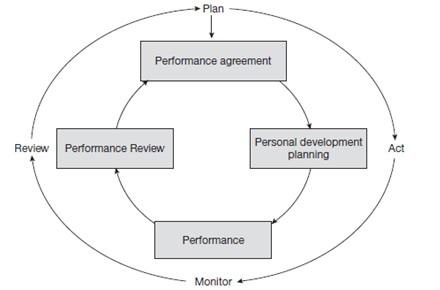

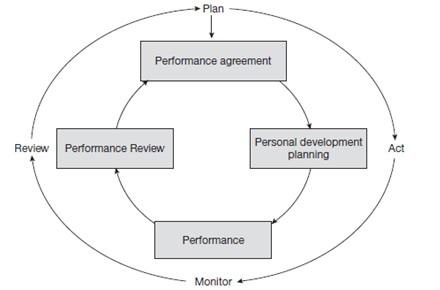

In this chapter, let us understand the process of performance management. Performance management is a process management which consists of the following activities −

Plan − decide what to do and how to do it.

Act − carry out the work needed to implement the plan.

Monitor − carry out continuous checks on what is being done and measure outcomes in order to assess progress in implementing the plan.

Review − consider what has been achieved and, in the light of this, establish what more needs to be done and any corrective action required if performance is not in line with the plan.

This sequence of activities can be expressed as a continuous cycle as shown in the following figure −

Performance Management Cycle

Performance management can be described as a continuous process cycle as shown in the following figure, which follows the plan–act–monitor–review sequence as described above.

Performance Management Sequence

The sequence of processes carried out in this cycle and the likely outcomes are illustrated in the following figure −

Performance Management Activities

Let us now discuss the activities that take place in performance management. The main activities are −

Role definition, in which the key result areas and competence requirements are agreed.

The performance agreement, which defines expectations − what individuals have to achieve in the form of objectives, how performance will be measured and the competences needed to deliver the required results.

The performance improvement plan, which specifies what individuals should do to improve their performance when necessary.

The personal development plan, which sets out the actions people should take to develop their knowledge and skills and increase their levels of competence.

Managing performance throughout the year, when action is taken to implement the performance agreement and performance improvement and personal development plans as individuals carry on with their day-to-day work and their planned learning activities. It includes a continuous process of providing feedback on performance, conducting informal progress reviews, updated objectives and, where necessary, dealing with performance problems.

Performance review is an evaluation stage, where a review of performance over a period takes place covering the aspects like achievements, progress and problems as the basis for the next part of the continuous cycle – a revised performance agreement and performance improvement and personal development plans. It can also lead to performance ratings.

Performance Management in Action

Performance management should not be like a system based on periodical formal appraisals and detailed documentation. The activities should be logical in the sense of contributing to an overall approach in which all aspects of the performance management process are designed.

Thus, in every organization there is a need to declare why performance management is important, how it works and how people will be affected by it. The declaration should have the visible and continuous support of top management and should emphasize to develop a high-performance culture and integrate organizational and individual goals.

Performance management recognizes the fact that we all create the view of the people who work for the organization and it also makes sense to express that view explicitly against a framework of reference.

Planning & Agreements

Performance management helps people to get into action so that they achieve planned and agreed results. It focuses on what has to be done, how it should be done and what is to be achieved. But it is equally concerned with developing people – helping them to learn – and providing them with the support they need to do well, now and in the future.

Performance Agreement

The framework for performance management is provided by the performance agreement, which is the outcome of performance and development planning. The agreement provides the basis for managing performance throughout the year and for guiding improvement and development activities.

The performance agreement is used as a reference point when reviewing performance and the achievement of improvement and development plans. Performance and development planning is carried out jointly by the manager and the individual. These discussions should lead to an agreement on what needs to be done by both parties.

The starting point for the performance and development plans is provided by the role profile, which defines the results, knowledge and skills and behaviors required. This provides the basis for agreeing objectives and performance measures. Performance and personal development plans are derived from an analysis of role requirements and performance in meeting them.

Role Profiles

The basis of the performance and development agreement is a role profile, which defines the role in terms of the key results expected, what role holders are expected to know and be able to do, and how they are expected to behave in terms of behavioral competencies and upholding the organization’s core values. Role profiles need to be updated every time a formal performance agreement is developed.

Developing Role Profiles

To develop a role profile, it is necessary for the line manager and the individual to get together and agree on the key result areas, define what the role holder needs to know and be able to do and ensure that there is mutual understanding of the behavioral competencies required and the core values the role holder is expected to uphold.

Defining Key Result Areas

When introducing performance management, it is probably best to figure out what is to be done rather than focusing on what has to be achieved.

To define key result areas, individuals should be asked the following questions by their managers −

- What do you think are the most important things you have to do?

- What do you believe you are expected to achieve in each of these areas?

- How will you – or anyone else – know whether or not you have achieved them?

The answers to these questions may need to be sorted out – they can often result in a mass of jumbled information that has to be analyzed so that the various activities can be distinguished and refined to seven or eight key areas.

This process requires some skill, which needs to be developed by training followed by practice. It is an area in which HR specialists can usefully coach and follow up on a oneto-one basis after an initial training session.

Defining Technical Competencies

To define technical competencies, i.e., what people need to know and be able to do; three questions need to be answered −

To perform this role effectively, what is it that the role holder should be able to do with regard to each of the key result areas?

What knowledge and skills in terms of qualifications, technical and procedural knowledge, problem-solving, planning and communication skills etc. do role holders need to carry out the role effectively?

How will anyone know when the role has been carried out well?

Defining Behavioral Competencies

The usual approach to including behavioral competencies in the performance agreement is to use a competency framework developed for the organization. The manager and the individual can then discuss the implications of the framework at the planning stage. The following is an example of a competence framework −

Personal drive − demonstrate the drive to achieve, acting confidently with decisiveness and resilience.

Business awareness − identifies and explores business opportunities, understand the business concerns and priorities of the organization and constantly seek methods of ensuring that the organization becomes more businesslike.

Teamwork − work cooperatively and flexibly with other members of the team with a full understanding of the role to be played as a team member.

Communication − communicate clearly and persuasively, orally or in writing.

Customer focus − exercise unceasing care in looking after the interests of external and internal customers to ensure that their wants, needs and expectations are met or exceeded.

Developing others − foster the development of members of his or her team, providing feedback, support, encouragement and coaching.

Flexibility − adapt to and work effectively in different situations and carry out a variety of tasks.

Leadership − guide, encourage and motivate individuals and teams to achieve a desired result.

Planning − decide on courses of action, ensuring that the resources required to implement the action will be available and scheduling the programme of work required achieving a defined end-result.

Problem solving − analysis situations, diagnose problems, identify the key issues, establish and evaluate alternative courses of action and produce a logical, practical and acceptable solution.

Core Values

Increasingly, performance management is being used by organizations to encourage people ‘to live the values’. These values can include such concerns as quality, continuous improvement, customer service, innovation, care and consideration for people, environmental issues and equal opportunity. Discussions held when the performance agreement is being reached can define what these values mean as far as individual behavior is concerned.

Assessing how well people uphold core values is an integral part of performance management, stating that −

Our success depends on all of us sharing the common values set out in the management plan, i.e. −

Integrity − We demonstrate high standards of honesty and reliability.

Impartiality − We are fair and even-handed in dealing with members of the public and each other.

Professionalism − We provide high quality professional advice and support services.

Client focus − We are responsive to the needs of members, the public and one another.

Efficiency − We use resources responsibly and cost-effectively.

Mutual respect − We treat everyone with respect and courtesy and take full account of equal opportunities issues at all times.

Objective Setting

Objectives describe something that has to be accomplished. Objectives or goals define what organizations, functions, departments and individuals are expected to achieve over a period of time. Objective setting those results in an agreement on what the role holder has to achieve is an important part of the performance management processes of defining and managing expectations and forms the point of reference for performance reviews.

Types of Objectives

Let us now understand the different types of objectives and how they are set. The following are the different types of objectives −

Ongoing Role or Work Objectives

All roles have built-in objectives, which may be expressed as key result areas in a role profile. A key result area shows us what the role holder is expected to achieve in this particular aspect of the role.

For example − ‘Identify database requirements for all projects that require data management in order to meet the needs of internal customers’ or ‘Deal quickly with customer queries in order to create and maintain high levels of satisfaction.’

A key result area statement should contain an indication of not only what has to be done but also why it has to be done. The ‘why’ part clarifies the ongoing objective but it may be necessary to expand that by reaching agreement on a performance standard that describes what good performance will look like.

A performance standard definition should take the form of a statement that performance will be up to standard if a desirable, specified and observable result happens. It should preferably be quantified in terms, for example, of level of service or speed of response.

Targets

Targets are objectives that define the quantifiable results to be attained as measured in terms such as output, throughput, income, sales, and levels of service delivery, cost reduction and reduction of reject rates. Thus, a customer service target could be to respond to 90 per cent of queries within two working days.

Tasks/projects

Objectives can be set for the completion of tasks or projects by a specified date or to achieve an interim result. A target for a database administrator could be to develop a new database to meet the need of the HR department by the end of the year.

Behavioral Expectations

Behavioral expectations are often set out generally in competency frameworks but they may also be defined individually under the framework headings. Competency frameworks may deal with areas of behavior associated with core values, for example, teamwork, but they often convert the aspirations contained in value statements into more specific examples of desirable and undesirable behavior, which can help in planning and reviewing performance.

Values

Expectations can be defined for upholding the core values of the organization. The aim would be to ensure that espoused values become values in use.

Performance Improvement

Performance improvement objectives define what needs to be done to achieve better results. They may be expressed in a performance improvement plan, which specifies what actions need to be taken by role holders and their managers.

Developmental/learning

Developmental or learning objectives specify areas for personal development and learning in the shape of enhanced knowledge and skills (abilities and competences).

Integrating the Objectives

A defining characteristic of performance management is the importance attached to the integration or alignment of individual objectives with organizational objectives. The aim is to focus people on doing the right things in order to achieve a shared understanding of performance requirements throughout the organization.

The integration of organizational and individual and team objectives is often referred to as a process of ‘cascading objectives’. However, cascading should not be regarded as just a top-down process.

There will be overarching corporate goals, but people at each level should be given the opportunity to indicate how they believe they can contribute to the attainment of team and departmental objectives. The views of employees towards organization about what they believe they can achieve and they should also take account of them.

There will be times when the overriding challenge has to be accepted, but there will also be many occasions when the opinions of those who have to do the work will be well worth listening to.

Integration of objectives is achieved by ensuring that everyone is aware of corporate, functional and team goals and that the objectives they agree for themselves are consistent with those goals and will contribute in specified ways to their achievement. This process is illustrated in the following figure.

Performance Measures & Assessements

It is often said that, if you can’t measure it, you can’t manage it and what gets measured, gets done. Certainly, you cannot improve performance until you know what present performance is. The process of managing performance begins by defining expectations in terms of targets, standards and competence requirements.

Improvements to performance have to start from an understanding of what the level of current performance is in terms of both results and competencies. This is the basis for identifying improvement and development needs in the individuals. Mainly, it provides the information required for career planning and continuous development by identifying strengths to be enhanced as well as weaknesses to be overcome.

This can only be achieved if there are reliable performance measures. Performance management also gives opportunities to good performers to take charge of their own performance. This cannot be done unless they can measure and monitor their own goals.

Measurement and assessment issues – outputs, outcomes and inputs

It can be argued that what gets measured is often what is easy to measure. And in some jobs what is meaningful is not measurable and what is measurable is not meaningful. It was asserted by Levinson that: ‘The greater the emphasis on measurement and quantification, the more likely the subtle, non-measurable elements of the task will be sacrificed. Quality of performance frequently, therefore, loses out to quantification.’

Measuring performance is relatively easy for those who are responsible for achieving quantified targets, for example sales. It is more difficult in the case of knowledge workers, for example scientists. But this difficulty is alleviated if a distinction is made between the two forms of results – outputs and outcomes.

Variations in performance measures

The focus for senior managers is likely to be based on definitions of key result areas that spell out their personal responsibility for growth, added value and results.

The performance of managers, team leaders and professional staff also is measured by reference to definitions of their key result areas. The achievement of quantitative targets is still important but more emphasis will be placed on competence requirements.

The focus of performance agreements and measures will vary considerably between different occupations and levels of management as shown in in the following figure.

In administrative, clerical jobs, performance measures will be related to key activities which continue standards of performance and work objectives which will be considered as the main source of measuring performance.

Performance Planning

The performance planning part of the performance management sequence consists of a joint exploration of what individuals are expected to do and know and how they are expected to behave to meet the requirements of their role and develop their skills and capabilities.

The plan also deals with how their managers will provide the support and guidance they need. It is forward looking, although an analysis of performance in the immediate past may provide guidance on areas for improvement or development.

The performance aspect of the plan obtains agreement on what has to be done to achieve objectives, raise standards and improve performance. It also establishes priorities – the key aspects of the job to which attention have to be given. These could be described as work plans, which set out programs of work for achieving targets, improving performance or completing projects.

The aim is to ensure that the meaning of the objectives and performance standards as they apply to everyday work is understood. They are the basis for converting aims into action.

Development Planning

For individuals, this stage includes the preparation and agreement of a personal development plan. This provides a learning action plan for which they are responsible with the support of their managers and the organization.

It may include formal training but, more importantly, it will incorporate a wider set of development activities such as self-managed learning, coaching, mentoring, project work, job enlargement and job enrichment. If multi-source assessment is practiced in the organization this will be used to discuss development needs.

The development plan records the actions agreed to improve performance and to develop knowledge, skills and capabilities. It is likely to focus on development in the current job – to improve the ability to perform it well and also, importantly, to enable individuals to take on wider responsibilities, extending their capacity to undertake a broader role.

This plan therefore, contributes to the achievement of a policy of continuous development, which is predicated on the belief that everyone is capable of learning more and doing better in their jobs. But the plan will also contribute to enhancing the potential of individuals to carry out higher-level jobs.

Performance Agreement

Performance agreement defines the following −

Role requirements − these are set out in the form of the key result areas of the role: what the role holder is expected to achieve.

Objectives − in the form of targets and standards of performance.

Performance measures and indicators − to assess the extent to which objectives and standards of performance have been achieved.

Knowledge, skill and competence − these define what role holders have to know and be able to do (competences) and of how they are expected to behave in particular aspects of their role (competencies). These definitions may be generic, having been prepared for occupations or job families on an organization- or function-wide basis. Role-specific profiles should, however, be agreed, which express what individual role holders are expected to know and do.

Corporate core values or requirements − the performance agreement may also refer to the core values of the organization for quality, customer service, team working, employee development etc., which individuals are expected to uphold in carrying out their work. Certain general operational requirements may also be specified in such areas as health and safety, budgetary control, cost reduction and security.

A performance plan − a work plan that specifies what needs to be done to improve performance.

A personal development plan − which specifies what individuals need to do with support from their manager to develop their knowledge and skills.

Process details − how and when performance will be reviewed and a revised performance agreement concluded.

Managing Performance

Perhaps one of the most important concepts of performance management is that it is a continuous process that reflects normal good management practices of setting direction, monitoring and measuring performance and taking action accordingly.

Performance management should not be imposed on managers as something ‘special’ they have to do. It should instead be treated as a natural function that all good managers carry out. To ensure that a performance management culture is built and maintained, performance management has to have the active support and encouragement of top management who must make it clear that it is regarded as a vital means of achieving sustained organizational success.

Importantly, the supporting process of performance management must be converted into reality by the deeds as well as the words of the people who have the ultimate responsibility for running the business.

Performance appraisal systems were usually built around an annual event. This is taken care by the personnel department of every organization.

The Continuing Process of Performance Management

Performance management should be regarded as an integral part of the continuing process of management. This is based on a philosophy that emphasizes −

the achievement of sustained improvements in performance;

the continuous development of skills and capabilities;

that the organization is a ‘learning organization’, in the sense that it is constantly developing and applying the learning gained from experience and the analysis of the factors that have produced high levels of performance.

Managers and individuals should therefore be ready, willing and able to define and meet development and improvement needs as they arise. As far as practicable, learning and work should be integrated. This means that encouragement should be given to all managers and members of staff to learn from the successes, challenges and problems inherent in their day today work.

The process of continuing assessment should be carried out by reference to agreed objectives and to work, development and improvement plans. Progress reviews can take place informally or through an existing system of team meetings. But there should be more formal interim reviews at predetermined points in the year, e.g. quarterly.

For some teams or individual jobs, these points could be related to ‘milestones’ contained in project and work plans. Deciding when such meetings should take place would be up to the individual managers in consultation with their staff and would not be a laid down part of a ‘system’.

Managers should encourage regular dialogue within the established pattern of briefing, team or group meetings or project review meeting. In addition to the collective meetings, managers may have regular one-to-one meetings with their staff.

If performance management is to be effective, there needs to be a continuing agenda through these regular meetings to ensure that good progress is being made towards achieving the objectives agreed for each key result area. During these interim meetings, progress in achieving agreed operational and personal objectives and associated work, development and improvement plans can be reviewed.

Interim review meetings should also be conducted along the lines of the main review meetings. Any specific outcomes of the meeting should be recorded as amendments to the original agreement and objectives and plans. Two of the main issues that may arise in the course of managing performance throughout the year are updating objectives and continuous learning.

Updating Objectives and Work Plans

Performance agreements and plans are working documents. New demands and new situations arise, and provisions therefore need to be made for updating or amending objectives and work plans. This involves −

discussing what the job holder has done and achieved;

identifying any shortfalls in achieving objectives or meeting standards;

establishing the reasons for any shortfalls, in particular examining changes in the circumstances in which the job is carried out, identifying new demands and pressures and considering aspects of the behavior of the individual or the manager that have contributed to the problem;

agreeing on changes required in objectives and work plans in response to prevailing circumstances;

agreeing on actions required by the individual or the manager to improve performance.

Continuous Learning

Performance management aims to enhance learning from experience — learning by doing. This means learning from the problems, challenges and successes inherent in people’s day-to-day activities.

This principle can be extended to any situation when managers give instructions to people or agree with them on what needs to be achieved, followed by a review of how well the task was accomplished. Such day-to day contacts provide training as well as learning opportunities and performance management emphasizes that these should be deliberate acts.

Let us consider two examples — one at the Team level and one at the Individual level.

Example 1

A team with the manager as project leader has the task of developing and implementing a new computerized system for responding to customer account queries. The team would start by jointly assessing with their leader their terms of reference, the project schedule, the budget and the results they are expected to deliver.

The team would then analyze progress and at periodical ‘milestone’ meetings would review what has or has not been achieved, agree on the lessons learnt and decide on any actions that need to be taken in the shape of modifications to the way in which they conduct the project for the future. Learning is an implicit part of these reviews because the team will be deciding on any changes it should make to its method of operation – learning can be defined as the modification of behavior through experience.

The team would need to adapt their behavior as required by the organization and what lessons have been learnt and how they need to behave in the future on the basis of this review.

The same approach would apply to individuals as well.

Example 2

The regional manager of a large sales company holds a monthly meeting with each of the field officers. At the meeting, progress is reviewed and problems discussed. Successes would be analyzed to increase the field officer’s understanding of what needs to be done to repeat the successful performance in the future.

These are examples of project or periodical work reviews. But continuous learning can take place even less formally, as when a team leader in an accounts department instructs an accounts assistant on her role in analyzing management information from the final assembly department as part of a newly introduced activity-based costing system.

The instructions will cover what has to be done and how, and the team leader will later check if the things are going as planned. This will provide an opportunity for further learning on the part of the accounts assistant, prompted by the team leader, in any aspect of the task where problems have occurred in getting it done properly.

Reviewing Performance

Performance review meetings are the means through which the five primary performance management elements — agreement, measurement, feedback, positive reinforcement and dialogue can be put to good use. The review should be rooted in the reality of the employee’s performance.

Every individual should be encouraged to assess their own performance and become active agents for change in improving their results. Managers should be encouraged to adopt their proper enabling role coaching and providing support and guidance.

There should be no surprises in a formal review if performance issues have been arising during the year. The true role of performance management is to look forward to what needs to be done by people to achieve the purpose of the job, to meet new challenges, to make even better use of their knowledge, skills and abilities, to develop their capabilities.

This process also helps managers to improve their ability to lead, guide and develop the individuals and teams. The most common practice is to have one annual review and twiceyearly reviews. These reviews lead directly into the conclusion of a performance agreement.

It can be argued that formal reviews are unnecessary and that it is better to conduct informal reviews as part of normal good management practice to be carried out as and when required. Such informal reviews are valuable as part of the continuing process of performance management (managing performance throughout the year as discussed in the previous chapter).

Performance Review Difficulties

In traditional merit rating or performance appraisal schemes, the annual appraisal meeting was the key event, in fact in most cases the only event, in the system. Line managers were often highly skeptical about the process, which they felt was imposed on them by the personnel department.

A typical reaction was: ‘Not another new appraisal scheme! The last three didn’t work.’ Managers felt that the schemes had nothing to do with their own needs and existed simply to maintain the personnel database.

Too often the personnel department contributed to this belief by adopting a ‘policing’ approach to the system, concerning them more with collecting completed forms and checking that each box has been ticked properly than with helping managers to use the process to improve individual and organizational performance.

The following are the three main sources of difficulty in conducting performance reviews −

The quality of the relationship between the manager and the individual − unless there is mutual trust and understanding the perception of both parties may be that the performance review is a daunting experience in which hostility and resistance are likely to emerge

The manner and the skill with which the interview is conducted

The review process itself − its purpose, methodology and documentation

Performance Review Issues

The following are the main issues concerning performance reviews −

- Why have them at all?

- If they are necessary, what are the objectives of reviewing performance?

- What are the organizational issues?

- On whom should performance reviews focus?

- On what should they focus?

- What criteria should be used to review performance?

- What impact does management style make on performance reviews?

- What skills are required to conduct reviews and how can they be developed?

- How can both negative and positive elements be handled?

- How can reviews be used to promote good communication?

- How should the outputs of review meetings be handled?

- To what extent is past performance a guide to future potential?

- When should reviews take place?

- What are the main problems in conducting reviews and how can they be overcome?

- How can their effectiveness be evaluated?

Organizational Issues

To have any chance of success, the objectives and methodology of performance reviews should either be in harmony with the organization’s culture or be introduced deliberately as a lever for change, moving from a culture of management by command to one of management by consent.

Performance management and review processes can help to achieve cultural change, but only if the change is managed vigorously from the top and every effort is made to bring managers and staff generally on board through involvement in developing the process, through communication and through training.

In short, when introducing performance management, you cannot work against the culture of the organization. You have to work within it, but you can still aspire to develop a performance culture, and performance management provides you with a means of doing so.

Performance Mngmt - Review Skills

Conducting an effective performance review is one in which problems of underperformance are discussed. This demands considerable skill on the part of the reviewer in such areas as giving feedback, agreeing objectives, assessing performance and development needs, planning for performance improvement and carrying on a dialogue.

One advantage of introducing an element of formality into the review process is that it highlights the skills required to carry out both formal and informal reviews and emphasizes the role of the manager as a coach. These skills come naturally to some managers. Others, probably the majority, will benefit from guidance and coaching in these key aspects of their managerial roles.

Criteria for Assessing Performance

The criteria for assessing performance should be balanced between −

- Achievements in relation to objectives

- The level of knowledge and skills possessed and applied

- Behavior in the job as it affects performance

- The degree to which behavior upholds the core values of the organization

- Day-to-day effectiveness

The criteria should not be limited to a few quantified objectives as has often been the case in traditional appraisal schemes. In many cases, the most important consideration will be the jobholders’ day-to-day effectiveness in meeting the continuing performance standards associated with their key tasks. It may not be possible to agree meaningful new quantified targets for some jobs every year. Equal attention needs to be given to the behavior that has produced the results as well as the results themselves.

Dealing with Positive and Negatives

This is probably the area of greatest concern to line managers, many of whom do not like handing out criticisms. Performance reviews should not be regarded as an opportunity for attaching blame for things that have gone wrong in the past.

If individuals have to be shown that they are accountable for failures to perform to standard or to reach targets, that should have been done at the time when the failure occurred, not saved up for the review meeting. And the positive elements should not be neglected. Too often they are overlooked or mentioned briefly then put on one side.

The following sequence is not untypical −

- Objective number one – fantastic.

- Objective number two – that was great.

- Objective number three – couldn’t have been done better.

- Now objective number four – this is what we really need to talk about. What went wrong?

If this sort of approach is adopted, the discussion will focus on the failure, the negatives, and the individual will become defensive. This can be destructive and explains why some people feel that the annual review meeting is going to be a ‘beat me over the head’ session.

Underemphasizing the positive aspects reduces the scope for action and motivation. More can be achieved by building on positives than by reviewing performance concentrating on the negatives. People are most receptive to the need for further learning when they are talking about success.

Empowering people is a matter of building on success. But this does not mean that underperformance should go unnoticed. Specific problems may have been dealt with at the time but it may still be necessary to discuss where there has been a pattern of underperformance. The first step, and often the most difficult one, is to get people to agree that there is room for improvement.

This will best be achieved if the discussion focuses on factual evidence of performance problems. Some people will never admit to being wrong and in those cases you may have to say in effect that ‘Here is the evidence; I have no doubt that this is correct; I am afraid you have to accept from me on the basis of this evidence that your performance in this respect has been unsatisfactory.’

If at all possible, the aim is not to blame people but to take a positive view based on obtaining answers to questions such as these −

- Why do you think this has been happening?

- What do you think you can do about it?

- How can I help?

Using Review as a Communication Channel

A well-conducted review meeting provides ‘quality time’ in which individuals and their managers can discuss matters affecting work and future developments. They also provide an extra channel of communication. Properly planned review meetings allow much more time and space for productive conversation and communication than is generally available to busy managers – this is perhaps one of their most important purposes.

There should be ample scope for communication about the organization’s or department’s objectives and how individuals fit into the picture – the contribution they are expected to make. Information can be given on significant events and changes in the organization that will impact on the role of the department and its members.

One of the objections that can be made to this free flow of information is that some of it will be confidential. But the need for confidentiality is often overstated. If the feeling is conveyed to people that they cannot be trusted with confidential information it will not do much for their motivation.

Balancing Past Performance against Future Potential

Traditionally, line managers have been asked to predict the potential for promotion of their subordinates. But that has put them in a difficult position unless they have a good understanding of the requirements (key dimensions and capabilities) of the roles for which their staff may have potential. This is unlikely in many cases, although the development of ‘career maps’ setting out the capabilities required in different roles and at different levels can provide invaluable information.

In general terms, past performance is not necessarily a good predictor of potential unless it contains performance related to dimensions that are also present in the anticipated role.

Because of these problems, assessments of potential are now less frequently included as part of the performance review meeting. They are more often carried out as a separate exercise, sometimes by means of assessment centers.

Evaluating Performance Reviews

There is no doubt that in spite of careful training and guidance some managers will be better at conducting performance review meetings than others. So how can their performance as performance reviewers be evaluated as a basis for further training or guidance when necessary?

There are different approaches to evaluating performance reviews −

The traditional approach

Traditionally, the personnel department had a policing role – checking that performance appraisal forms are completed on time and filled in properly. However, this will convey nothing about the quality of the meeting or the feelings of individuals after it – they may have signed the form to agree with its comments but this does not reveal what they really thought about the process.

Alternate approach

Another approach is to get the manager’s manager (the so-called ‘grandparent’) to review the form. This at least provides the individual who has been reported on with the comfort of knowing that a prejudiced report may be rejected or amended by a higher authority. But it still does not solve the problem of a negative or biased review process, which would probably not be conveyed in a written report.

Space on the review form can be given to individuals to comment on the review, but many will feel unwilling to do so. If the interview has been conducted in an intimidating manner, how ready are they likely to be to commit themselves to open criticism?

Another productive approach

This approach is to conduct an attitude survey following performance reviews asking individuals in confidence to answer questions about their review meeting such as −

- How well did your manager conduct your performance review meeting?

- Are there any specific aspects of the way in which the review was conducted that could be improved?

- How did you feel at the end of it?

- How are you feeling at the moment about your job and the challenges ahead of you?

- How much help are you getting from your manager in developing your skills and abilities?

The results of such a survey, a form of upward assessment, can be fed back anonymously to individual managers and, possibly, their superiors, and action can be taken to provide further guidance, coaching or formal training. A general analysis of the outcome can be used to identify any common failings, which can be dealt with by more formal training workshops.

Assessing Performance

Let us understand the different ways to assess performance in this chapter.

Approaches to Assessment

Performance management is forward looking. It focuses on planning for the future rather than dwelling on the past. But it necessarily includes some form of assessment of what has been achieved to provide the basis for performance agreements and development plans, forecasts of potential and career plans.

In addition, a performance management process commonly, but not inevitably, incorporates a rating or other means of summing up performance to encapsulate views about the level of performance reached and, if required, inform performance-or contribution-related pay decisions.

Factors Affecting Assessments

Assessments require the ability to judge performance, and good judgment is a matter of using clear standards, considering only relevant evidence, combining probabilities in their correct weight and avoiding projection.

Most managers think they are good judges of people

One seldom if ever meets anyone who admits to being a poor judge, just as you seldom meet anyone who admits to being a bad driver, although accident rates suggest that bad drivers do exist and mistakes in selection, placement and promotion indicate that some managers are worse than others in judging people.

Different managers will assess the same people very differently unless, with difficulty, a successful attempt to moderate their views is made. This is because managers assessing the same people will tend to assess them against different standards. Managers may jump to conclusions or make snap judgments if they are just required to appraise and rate people rather than to conduct a proper analysis of performance.

The halo or horns effect can apply when the manager is aware of some prominent or recent example of good or poor performance and assumes from this that all aspects of the individual’s performance are good or bad.

Is it simply what people produce – their output? Or is it how they produce it – their behavior? Or is it both? It is, in fact, both, but not everyone recognizes that, and this results in suspect assessments.

To overcome these problems, it is necessary to −

ensure that the concept of performance and what constitutes good and not-sogood performance is understood by all concerned, managers and employees alike

encourage managers to define and agree standards and measures of effectiveness beforehand with those concerned

encourage and train people to avoid jumping to conclusions too quickly by consciously suspending judgment until all the relevant data available have been examined

provide managers with practice in exercising judgments that enable them to find out for themselves their weaknesses and thus improve their techniques

Narrative Assessment

A narrative assessment is simply a written summary of views about the level of performance achieved. This at least ensures that managers have to collect their thoughts together and put them down on paper. But different people will consider different aspects of performance and there will be no consistency in the criteria used for assessment.

Traditionally this was a top-down process – managers in effect told their staff what they thought about them or, worse still, recorded their judgments without informing their staff. This autocratic approach may be modified by giving individuals the opportunity to comment on their managers’ judgments. Or, better still, the summary could be jointly prepared and agreed.

The danger is that managers will tend to produce bland, generalized and meaningless assessments that provide little or no guidance on any action required. A few suggested careful thought and a conscientious effort to say something meaningful, but the vast majorities were remarkable for their neutrality.

Typical of such statements was a loyal, conscientious and hard-working employee. Such a statement may well have been true but it is not very revealing. Two ways have been used to alleviate this problem. The first traditional method was to issue guidelines that set out the points to be covered.

The guidelines asked managers to comment on a number of defined characteristics, for example industry and application, loyalty and integrity, cooperation, accuracy and reliability, knowledge of work and use of initiative.

When assessing a characteristic such as industry and application, managers might have been asked to: ‘Consider the individual’s application to work and the enthusiasm with which tasks were undertaken.’ In practice, however, guidelines of this type were so vague that comments were uninformative. This approach is now therefore largely discredited although it lingers on in some old-established schemes.

The second method is to ask for comments on the extent to which agreed objectives have been achieved, to which may be added comments on behavior against competency framework headings. At least this is related to standards against which judgments are made but the efficacy of doing it is questionable.

The only reason for including a narrative assessment is to point the way to future action, and this will not be achieved by simply putting a few comments down on paper. It is better to provide for action plans to emerge from the systematic analysis of performance in terms of outcomes and behavior that should take place during the course of a review meeting.

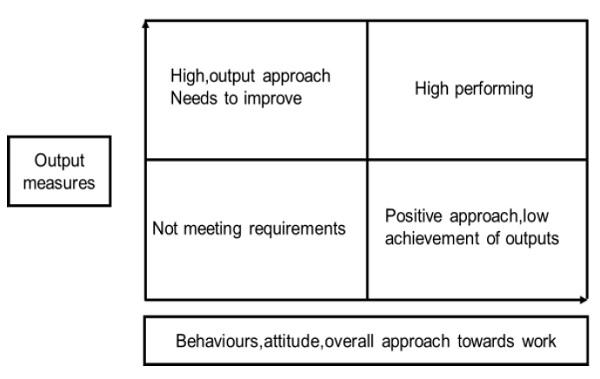

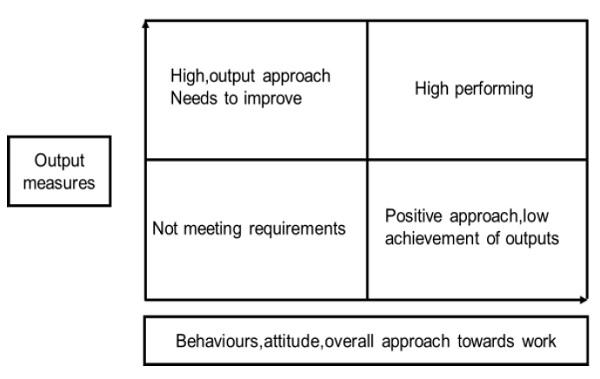

Visual Methods of Assessment

An alternative approach to rating is to use a visual method of assessment.

This takes the form of an agreement between the manager and the individual on where the latter should be placed on a matrix or grid, as illustrated in the following figure.

This is presented visually and as such provides a better basis for analysis and discussion than a mechanistic rating. The assessment of contribution refers both to outputs, and to behaviors, attitudes and overall approach.

The review guidelines accompanying this matrix are as follows −

You and your manager need to agree for an overall assessment. This will be recorded in the summary page at the beginning of the review document. The aim is to get a balanced assessment of your contribution through the year. The assessment will take account of how you have performed against the responsibilities of your role as described in the Role Profile; objectives achieved and competency development over the course of the year. The assessment will become relevant for pay increases in the future.

The grid on the annual performance review summary is meant to provide a visual snapshot of your overall contribution. This replaces a more conventional rating scale approach. It reflects the fact that your contribution is determined not just by results, but also by your overall approach towards your work and how you behave towards colleagues and customers.

The evidence recorded in the performance review will be used to support where your manager places a mark on the grid. Their assessment against the vertical axis will be based on an assessment of your performance against your objectives, performance standards described in your role profile, and any other work achievements recorded in the review.

Together these represent ‘outputs’. The assessment against the horizontal axis will be based on an overall assessment of your performance against the competency level definitions for the role.

Note that someone who is new in the role may be placed in one of the lower quadrants but this should not be treated as an indication of development needs and not as a reflection on the individual’s performance.

Other Approach

A similar ‘matrix’ approach has been adopted by Halifax BOS. It is used for management appraisals to illustrate their performance against peers. It is not an ‘appraisal rating’ – the purpose of the matrix is to help individuals focus on what they are well at and also on any areas for improvement.

Two dimensions – business performance and behavior (management style) – are reviewed on the matrix, as illustrated in the following, to ensure a rounder discussion of overall contribution against the full role demands rather than a short-term focus on current results.

Improving Performance

Improving Performance at the Organizational Level

It is tempting for managements to say that poor performance is always someone else’s fault, never theirs. But poor performance may be a result of inadequate leadership, bad management or defective systems of work. It is not necessarily the fault of employees.

The failure can be at the top of the organization because well-defined and unequivocal expectations for superior performance have not been established and followed through. And effective processes of performance management can provide a valuable means of communicating these expectations.

The Problems at Managerial Level

There are a variety of psychological mechanisms that managers sometimes use to avoid the unpleasant truth that performance gaps exist. The psychological mechanisms have been described as follows −

Evasion through rationalization

Managers may escape having to demand better performance by convincing themselves that they have done all they can to establish expectations. They overlook the possibility of obtaining greater yields from available resources.

When they do ask for more they are too ready to believe their staff when they claim that they are already overloaded, and they may weakly take in the extra work themselves. Or, they may go to the opposite extreme and threaten workers with arbitrary demands, unaccompanied by specifications of requirements and deadlines for results.

Reliance on procedures

Managers may rely on a variety of procedures, programs and systems to produce better results. Top managers say, in effect, ‘Let there be performance-related pay, or performance management’ and sit back to wait for these panaceas to do the trick – which, of course, they won’t unless they are part of a sustained effort led from the top, and are based on a vision of what needs to be done to improve performance.

Attacks that skirt the target

Managers may set tough goals and insist that they are achieved, but still fail to produce a sense of accountability in employees or provide the support required to achieve the goals.

Top Management Levers for Improving Performance

To improve organizational performance, top management needs to focus on developing a high-performance culture.

The characteristics of such a culture are −

a clear line of sight exists between the strategic aims of the organization and those of its departments and its staff at all levels;

management defines what it requires in the shape of performance improvements, sets goals for success and monitors performance to ensure that the goals are achieved;

leadership from the top that engenders a shared belief in the importance of continuous improvement;

focus on promoting positive attitude that results in a committed, motivated and engaged workforce.

The momentum for the creation of a high-performance culture has to be provided by the top management. There is a clear sense of mission underpinned by values and a culture expressing what the firm is and its relationship with its customers and employees.

Strong values provide the basis for both the management of performance and the management of change. These values have to be embedded, connected, enduring, collective and measured and managed.

The Sears Performance Model

The means by which a business achieves high performance was modelled by Sears, the retailing companies, as shown in the following figure.

This model emphasizes the importance of employee attitude and behavior in making the firm ‘a compelling place to shop’ and ultimately ‘a compelling place to invest’.

Improving Team Performance

A performance management approach to teamwork can be used to improve team performance in the following areas −

Setting Objectives

Team objectives can be concerned either with the achievement of work targets and standards or with the way in which the team operates.

Work Objectives

Work objectives for teams are formulated in the same way as individual objectives. They may be related to the mission and overall objectives of the organization and the function, unit or department in which the team operates.

The objectives may also be concerned with a specific project or area of activity that is not catered for separately in the objectives of any one department but will be supporting the attainment of an overarching objective of the organization, the unit or the function.

The team should agree on its overall mission or purpose and then on the specific objectives that will support the accomplishment of that mission. In some cases, team objectives will be completely integrated with organizational or functional/departmental objectives, depending on the nature of the team. In these circumstances, the team could make a major contribution to the formulation of overall objectives and would thus play a positive and active part in an upwardly directed objective-setting process.

Team working objectives

Team working objectives could be agreed on such matters as working together, contribution of team members, decision making and getting into action.

Work plans

It is important for teams to get together to create plans for achieving their agreed objectives. Work plans will specify programs (staged as necessary), priorities, responsibilities, timetables, budgets and arrangements for monitoring performance, feedback and holding progress meetings.

Work plans can also be useful for the team to discuss the critical success factors — what must be done and how it must be done if its mission and objectives are to be attained.

Team performance reviews

Team performance review meetings analyzes and assesses feedback and control information on their joint achievements against objectives and work plans.

The agenda for such a meeting could be as follows −

General review − of the progress of the team as a whole.

Work review − the results obtained by the team and how well it has worked together.

Group problem-solving − an analysis of reasons for any major problems and agreement of steps to be taken to solve them or to avoid their reoccurrence in the future.

Updating of objectives and work plans − review of new requirements, and amendment and updating of objectives and work plans.

Improving Individual Performance

To improve performance, therefore, attention has to be paid to −

increasing ability − by recruitment (people will want to join the organization), selection (choosing the right people) and learning and developing (people will want to enhance their knowledge and skills);

increasing motivation − by the provision of extrinsic and intrinsic rewards;

increasing opportunity − by providing people with the opportunity to use, practice and develop their skills.

The opportunity to engage in discretionary behavior is crucial if employees are to perform well. Discretionary behavior takes place when employees exercise choice on the range of tasks to be done and how they do their work, covering such aspects as effort, speed, care, attention to quality, customer service, innovation and style of job delivery.

The Bath team pointed out that: ‘Managing performance through people means finding ways to induce employees to work better or more effectively by triggering the discretionary behavior that is required. This happens when people find their jobs satisfying, they feel motivated and they are committed to their employer in the sense of wishing to stay working for the organization in the foreseeable future.’

Much of what needs to be done to improve individual performance happens at the organizational level. It is about developing a performance culture, providing leadership, creating the right working environment and generally adopting ‘the big idea’ as explained earlier in this chapter.

At the individual level, improvement in performance can also be achieved through policies and practices designed to increase learning by coaching, mentoring and self-managed learning. The aim should be to increase ‘discretionary learning’, which happens when individuals actively seek to acquire the knowledge and skills required to achieve the organization’s objectives.