DBMS - Data Recovery

Crash Recovery

DBMS is a highly complex system with hundreds of transactions being executed every second. The durability and robustness of a DBMS depends on its complex architecture and its underlying hardware and system software. If it fails or crashes amid transactions, it is expected that the system would follow some sort of algorithm or techniques to recover lost data.

Failure Classification

To see where the problem has occurred, we generalize a failure into various categories, as follows −

Transaction failure

A transaction has to abort when it fails to execute or when it reaches a point from where it can’t go any further. This is called transaction failure where only a few transactions or processes are hurt.

Reasons for a transaction failure could be −

Logical errors − Where a transaction cannot complete because it has some code error or any internal error condition.

System errors − Where the database system itself terminates an active transaction because the DBMS is not able to execute it, or it has to stop because of some system condition. For example, in case of deadlock or resource unavailability, the system aborts an active transaction.

System Crash

There are problems − external to the system − that may cause the system to stop abruptly and cause the system to crash. For example, interruptions in power supply may cause the failure of underlying hardware or software failure.

Examples may include operating system errors.

Disk Failure

In early days of technology evolution, it was a common problem where hard-disk drives or storage drives used to fail frequently.

Disk failures include formation of bad sectors, unreachability to the disk, disk head crash or any other failure, which destroys all or a part of disk storage.

Storage Structure

We have already described the storage system. In brief, the storage structure can be divided into two categories −

Volatile storage − As the name suggests, a volatile storage cannot survive system crashes. Volatile storage devices are placed very close to the CPU; normally they are embedded onto the chipset itself. For example, main memory and cache memory are examples of volatile storage. They are fast but can store only a small amount of information.

Non-volatile storage − These memories are made to survive system crashes. They are huge in data storage capacity, but slower in accessibility. Examples may include hard-disks, magnetic tapes, flash memory, and non-volatile (battery backed up) RAM.

Recovery and Atomicity

When a system crashes, it may have several transactions being executed and various files opened for them to modify the data items. Transactions are made of various operations, which are atomic in nature. But according to ACID properties of DBMS, atomicity of transactions as a whole must be maintained, that is, either all the operations are executed or none.

When a DBMS recovers from a crash, it should maintain the following −

It should check the states of all the transactions, which were being executed.

A transaction may be in the middle of some operation; the DBMS must ensure the atomicity of the transaction in this case.

It should check whether the transaction can be completed now or it needs to be rolled back.

No transactions would be allowed to leave the DBMS in an inconsistent state.

There are two types of techniques, which can help a DBMS in recovering as well as maintaining the atomicity of a transaction −

Maintaining the logs of each transaction, and writing them onto some stable storage before actually modifying the database.

Maintaining shadow paging, where the changes are done on a volatile memory, and later, the actual database is updated.

Log-based Recovery

Log is a sequence of records, which maintains the records of actions performed by a transaction. It is important that the logs are written prior to the actual modification and stored on a stable storage media, which is failsafe.

Log-based recovery works as follows −

The log file is kept on a stable storage media.

When a transaction enters the system and starts execution, it writes a log about it.

<Tn, Start>

<Tn, X, V1, V2>

It reads Tn has changed the value of X, from V1 to V2.

- When the transaction finishes, it logs −

<Tn, commit>

The database can be modified using two approaches −

Deferred database modification − All logs are written on to the stable storage and the database is updated when a transaction commits.

Immediate database modification − Each log follows an actual database modification. That is, the database is modified immediately after every operation.

Recovery with Concurrent Transactions

When more than one transaction are being executed in parallel, the logs are interleaved. At the time of recovery, it would become hard for the recovery system to backtrack all logs, and then start recovering. To ease this situation, most modern DBMS use the concept of 'checkpoints'.

Checkpoint

Keeping and maintaining logs in real time and in real environment may fill out all the memory space available in the system. As time passes, the log file may grow too big to be handled at all. Checkpoint is a mechanism where all the previous logs are removed from the system and stored permanently in a storage disk. Checkpoint declares a point before which the DBMS was in consistent state, and all the transactions were committed.

Recovery

When a system with concurrent transactions crashes and recovers, it behaves in the following manner −

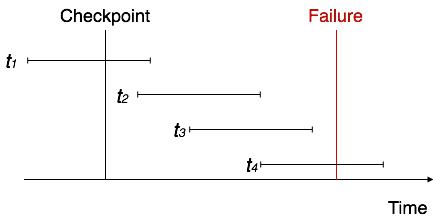

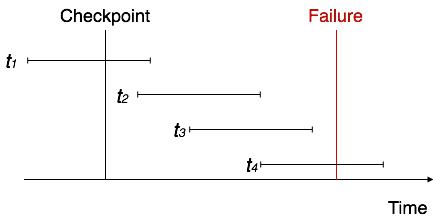

The recovery system reads the logs backwards from the end to the last checkpoint.

It maintains two lists, an undo-list and a redo-list.

If the recovery system sees a log with <Tn, Start> and <Tn, Commit> or just <Tn, Commit>, it puts the transaction in the redo-list.

If the recovery system sees a log with <Tn, Start> but no commit or abort log found, it puts the transaction in undo-list.

All the transactions in the undo-list are then undone and their logs are removed. All the transactions in the redo-list and their previous logs are removed and then redone before saving their logs.